Artificial intelligence detects wrist fractures

Artificial intelligence (AI) is used in an increasing number of domains. The computer-based data processing systems help to make work processes more effective and faster. Some even see AI systems as the future of the working world turned upside down, with the human factor soon to be replaced by the computer. At the same time, the internet laughs at AI software that cannot tell a cat from a dog. Has AI even outgrown its infancy yet? Indeed, with the help of machine learning, large amounts of data can already be analysed and processed accurately today. Medicine also benefits from this.

At the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Traumatology, the research centre in cooperation with AUVA (LBI Trauma), scientists have investigated whether the evaluation of X-ray images of wrist fractures by an AI programme actually provides results that are as reliable as the diagnosis by an experienced doctor.

The distal radius fracture, a fracture of the radius, is the most common fracture in adults. If the fracture is subtle, such as a hairline fracture, diagnostic errors can occur. “Unfortunately, overlooked fractures are among the most common errors in diagnosis in the trauma department, where it is often stressful and the work pressure is high,” says Dr Rosmarie Breu, lead author of the study. Yet, trauma surgeons should be able to diagnose a fracture quickly in order to prevent, for instance concomitant injuries to the nerves. After all, an overlooked wrist fracture can have long-lasting medical consequences for those affected. Can artificial intelligence support doctors in their diagnosis by acting as a “second opinion”?

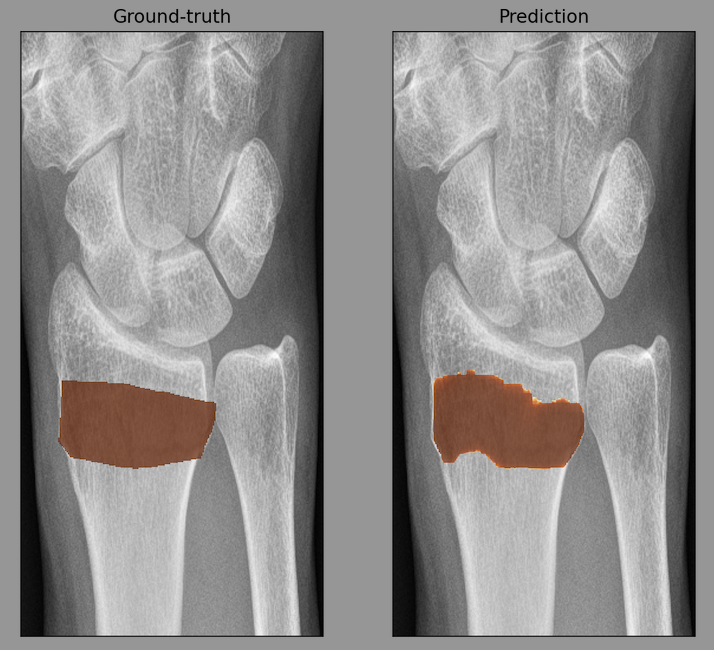

As part of a research project funded by the Vienna Business Agency, LBI Trauma and the company ImageBiopsy Lab have developed software that transforms X-ray images with corresponding findings into a statistical model. For the comparative study, the AI software was “trained” with around 20,000 anonymised X-ray images of the wrist with and without fractures. During this process, the software learns from human experts which images show a fracture and how they differ from images without a fracture.

Nine medical specialists, among who four are in training, then evaluated 200 randomly selected X-ray images of the wrist. “They first assessed the images without support,” Breu explains. Three weeks later, they assessed the same images again with the help of the AI software as a second opinion, the orthopaedist continues. The error rate in the diagnosis improved by around five percent with the support of artificial intelligence – the improvement was even more pronounced for doctors in training. These young doctors in particular were able to improve their diagnostic accuracy with the second opinion. With the AI software, they had the experience of their colleagues at hand, so to speak, who had trained the AI.

The researchers conclude from the data that the AI second opinion can improve an accurate diagnosis of wrist fractures that are difficult to see. What also becomes clear, however, is that the software is only as good as its trainers. It cannot outperform experienced doctors or even clinical examinations. As much hype as there is currently everywhere about AIs and their possibilities, humans as experts will remain irreplaceable in medicine for a long time to come.

What could the use of this AI look like in everyday clinical practice? “Ideally, the AI programme supports and optimises medical processes in the accident and emergency department,” says Breu. In addition to a significant reduction in missed fractures, diagnoses could be made faster and more accurately thanks to the AI second opinion. Until that happens, clinical studies have to test the accuracy and usefulness of artificial intelligence in diagnosing. In a next step, LBI Trauma wants to test the AI software in the detection of fractures in other regions of the body.